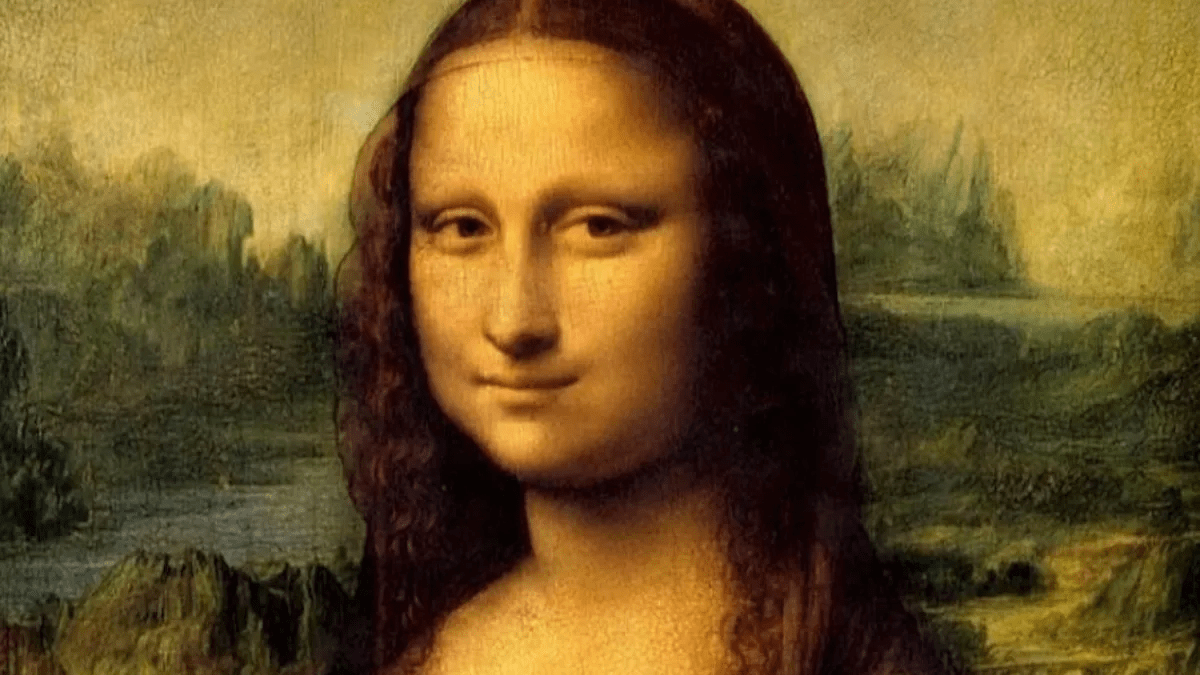

A team of Italian scientists is planning to reassemble the skull of Lisa Gherardini, the 15th-century Italian woman believed to be the model for Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa.

The aim is to determine whether the mysterious smile in the painting is truly hers.

No scientific study has yet confirmed that it is possible to accurately depict a smile from a person’s own skull, but in fact, it is possible to create an accurate outline of a person’s mouth from the remaining skull bone. Since the corners of our lips are based on the outer edges of our canines, the structure of the skull can tell us the width of the mouth, while the angle and contact points between the upper and lower jaws tell us how the lips meet, and the enamel of an adult’s teeth can tell us the thickness of the lips. If these features do not match the lines on Leonardo da Vinci’s drawing, scientists can make a convincing conclusion that Lisa Gherardini was not Leonardo da Vinci’s “muse.” However, proving that Gherardini was the model for Mona Lisa’s legendary smile remains difficult, because a human skull tells us very little about how someone smiles. Most of the muscles that control smiling are software, and each person’s smile is a conditioned reflex, rather than a natural product of bone structure.

Facial reconstruction techniques are hoped to unlock the mystery behind the Mona Lisa’s smile.

Forensic science has come a long way in facial reconstruction over the past few decades. Scientists can now recreate the shape of someone’s face, the position of their eyes, the slope of their nose, or the curve of their jaw to within a few millimeters. However, the problem is that it is difficult to identify someone from a face reconstructed from so many features. Scientists have tried using medical scanning technology to create a 3D image of a living person’s skull and reconstruct the shape of their face from that 3D image, but it has also been difficult to identify a reconstructed face.

In a 2001 study, Australian forensic anthropologists used reconstruction technology to create 16 faces from four skulls, then challenged inexperienced observers to pick out a photo of a deceased person from a set of 10. The observers ultimately failed. The subjects identified only one of the 16 reconstructed faces. Other studies have shown that even people who know them have difficulty identifying reconstructed faces. Science has advanced greatly in the past decade, but forensic reconstructionists are still better at creating hypothetical images of human ancestors than faithfully recreating modern faces.

Furthermore, plans to recreate the face of the real Mona Lisa face will face other challenges. Gherardini was over 60 years old when she died (around 1551). Facial reconstructionists have a few techniques for “reversing” someone’s age, such as the peaks of the eyebrows, which are more obvious in older people. But crucially, Gherardini’s skull lacks teeth. If Gherardini’s gums were bare when she died, that would have foiled the idea of recreating her mouth.

Ultimately, despite Leonardo da Vinci’s reputation for retouching and “anatomizing” portraits, the Mona Lisa is still just a painting. It’s unclear whether Leonardo intended it to be a realistic image or a more iconographic version of his subject. Furthermore, Leonardo worked on the painting for years, which made the task of faithfully recreating every angle of his “muse’s” face extremely difficult.

OTHER NEWS